Erasing the Memory, the Nation’s Father: The

Assault on Liberation War of Bangladesh

Abstract:

This study critically

investigates the deliberate erasure of national memory through the political

and symbolic assault on the legacy of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—widely

regarded as the Father of the Nation in Bangladesh. Framed within the broader

dynamics of authoritarianism, historical revisionism, and identity politics,

the research explores how successive regimes—especially military and

authoritarian governments following the 1975 coup—systematically marginalized,

distorted, or erased Bangabandhu’s role in the country's founding narrative.

This erasure took multiple forms, including the suppression of his image in

state media, the exclusion of his name from textbooks, the dismantling or

renaming of public monuments, and the silencing of commemorative practices.

Drawing on

archival documents, educational policy reviews, state propaganda materials, and

interviews with historians and political actors, this study reveals how

state-sponsored amnesia became a tool to forge alternative nationalist

ideologies while legitimizing autocratic rule. The paper engages with

theoretical frameworks on memory, symbolic power, and political repression to

demonstrate how erasing the “father” of the nation was not merely an act of

forgetting but a strategic move to redefine the nation's ideological

foundation. It also highlights the persistence of counter-narratives,

resistance by civil society, and the eventual partial recovery of Bangabandhu’s

legacy in the post-authoritarian era.

The research

underscores the fragility of collective memory in postcolonial societies and

calls for inclusive, pluralistic memory policies to resist authoritarian

manipulation. It contributes to interdisciplinary debates on memory politics,

historical justice, and the weaponization of forgetting.

Keywords:

Memory politics, Historical erasure, Bangladesh, Symbolic violence, National

identity, State repression, Collective memory, Transitional justice.

1. Introduction

1.1 The Power of Memory in Postcolonial

Nations

Memory is not merely a recollection of the

past—it is a socio-political act,

a lens through which nations define their present and shape their future.

Particularly in postcolonial states,

where the battle for legitimacy is ongoing, the politics of memory becomes a powerful mechanism for state-building, identity formation, and ideological reproduction. The past is

not fixed but constantly contested, as competing regimes seek to legitimize

their rule by privileging certain narratives and marginalizing others (Hobsbawm

& Ranger, 1983; Nora, 1989). In this context, historical figures such as Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the undisputed

architect of Bangladesh’s independence, become central to the memory wars of the nation.

Bangladesh’s trajectory since its birth in

1971 illustrates how collective memory is a terrain of ideological struggle. Few

leaders in South Asian political history embody national sentiment as

profoundly as Bangabandhu Sheikh

Mujibur Rahman. His name, image, and speeches are inextricably linked

with the birth of Bangladesh,

making him both a revered symbol

and a target for erasure. Over

the decades, especially under authoritarian

and military regimes, Bangabandhu’s legacy has been subjected to

erasure, revisionism, and politicized re-contextualization. His memory, housed

in Dhanmondi 32, has been as

much a shrine of national mourning as it has been a battlefield of historical

distortion.

1.2 Memory, Nationalism, and Political

Violence

National memory is often curated through

symbolic figures who embody the state’s foundational myths. These figures are

preserved through rituals, textbooks, statues, museums, and national holidays

(Assmann, 2011; Connerton, 1989). Yet such memory is also vulnerable to

political shifts—particularly under authoritarian

regimes, where memory erasure or

manipulation becomes a tool to reconstruct political legitimacy (Olick

& Robbins, 1998). The erasure of

political memory, especially that of revolutionary leaders, is rarely

accidental. It is a strategic effort to depoliticize

national consciousness, obscure

historical injustice, and silence

dissent.

This practice is not unique to Bangladesh.

In post-Soviet Russia, Stalinist monuments were removed and later partially

reinstated under Putin’s hybrid regime (Tumarkin, 1997). In South Africa, the

legacy of Steve Biko was suppressed during apartheid and revived post-1994 as

part of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In Sri Lanka, Tamil histories

were effaced to support Sinhala Buddhist nationalism (Spencer, 2008). These

examples show how authoritarianism

often targets symbolic figures whose memory challenges its ideological

coherence.

1.3 The Significance of Bangabandhu’s

Legacy

Sheikh Mujibur

Rahman,

popularly known as Bangabandhu (Friend of Bengal), holds a status in Bangladesh

akin to George Washington in the U.S.,

Mahatma Gandhi in India, or Nelson Mandela in South Africa. He was

the driving force behind the Six-Point

Movement (1966), the 7 March

1971 speech, and the Liberation

War of 1971. As the first Prime Minister and later President of

Bangladesh, his efforts laid the groundwork for a sovereign, secular, and inclusive republic.

However, his assassination in 1975 and the

subsequent rise of military-backed

regimes introduced a new phase in Bangladeshi political memory—one marked by repression, revisionism, and

erasure. The banning of his image, the deletion of his name from

textbooks, the prohibition of public commemorations, and the legal protection

given to his assassins (via the Indemnity

Ordinance) were calculated efforts to rewrite the foundational narrative of the country (Kamal, 2005).

These actions amounted to a symbolic ‘second

assassination’—an attempt to eliminate Bangabandhu not just physically,

but ideologically.

1.4 Dhanmondi 32: A Site of Memory and

Resistance

The house located at 32 Dhanmondi Road, where Bangabandhu

lived and was assassinated with most of his family members, has become a symbolic and emotional nucleus of

Bangladeshi memory. In the words of Nora (1989), Dhanmondi 32 is a ‘lieu de mémoire’—a site where memory

crystallizes and endures. It is not just a building of bricks, rods, and

cement, but a sacred site of sacrifice,

a space of martyrdom and mourning,

and a repository of collective grief.

Following the restoration of democracy in

the 1990s, the house was transformed into the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum, symbolizing the re-inscription of

memory into the nation’s fabric. However, even this physical site has faced

renewed threats. In 2024, an unconstitutional

regime, seeking to deconstruct the Liberation War narrative, targeted

Dhanmondi 32—cutting off utilities, dismantling its walls, and obstructing

commemorative events. These assaults on memory were not merely

administrative—they were acts of

symbolic violence intended to de-legitimize the historical authority of

Bangabandhu and his descendants.

1.5 Erasure as Authoritarian Practice

Erasure is an act of political violence.

Whether by removing names from history books, banning commemorative practices,

or physically destroying monuments, authoritarian regimes engage in epistemic warfare—the destruction of

knowledge, memory, and symbolic continuity (Mbembe, 2003; Foucault, 1977). The erasure of Bangabandhu follows this

pattern.

Between 1975 and 1996, military-backed regimes in Bangladesh

sought to impose a ‘value-neutral’

historical narrative—one that omitted the personalized, emotional, and

moral dimension of Bangabandhu’s leadership. His image was replaced by abstract nationalism, and his legacy

diluted into a generic war narrative where leadership was anonymous. This

approach conveniently allowed former collaborators

of the Pakistan regime to return to political prominence without

reckoning with historical accountability.

The 2024 interim regime revived these tactics by attacking both the material and symbolic dimensions of

Bangabandhu’s legacy. Unlike the earlier erasure, which relied on suppression,

the newer model employed surveillance,

algorithmic censorship, and media

manipulation, attempting to sanitize the digital landscape of

pro-Bangabandhu sentiment. This new erasure reflects 21st-century authoritarianism, which is no longer reliant solely

on coercion but utilizes disinformation

and digital erasure to manufacture consensus (Bradshaw & Howard,

2019).

1.6 Legacy and Memory as Political Capital

Bangabandhu’s legacy continues to hold enormous political and emotional capital

in Bangladesh. His life is invoked during elections, state functions,

educational reforms, and international diplomacy. This symbolic power makes him

a threat to unelected or anti-liberation forces, who view his legacy as a hindrance to their legitimacy.

By erasing Bangabandhu, authoritarian

actors attempt to create a historical

vacuum—a space where alternative figures, ideologies, or fabricated

narratives can gain ground. The assault on his legacy is, therefore, an assault on Bangladesh’s very foundation.

It is not merely the erasure of a man, but the unmaking of a nation’s self-understanding.

1.7 Memory Resistance and the Politics of

Mourning

The erasure of Bangabandhu has never gone

uncontested. Each wave of suppression has been met with acts of memory resistance—from underground booklets in the 1980s

to mass commemorations after 1996 and, more recently, digital memorial movements in 2024 such as #SaveDhanmondi32 and

#BangabandhuLives. These responses demonstrate that memory is resilient—even when denied state protection, it survives

in oral histories, family traditions, and emotional geographies (Assmann, 2011).

This resistance also underscores the politics of mourning. To mourn

Bangabandhu is not merely to grieve his death—it is to assert the legitimacy of the Liberation War, to affirm the moral

vision of a secular and just Bangladesh, and to reject authoritarian forgetfulness. Mourning becomes a political act, reclaiming memory

from the jaws of erasure.

1.8 Research Aim and Scope

This article investigates the systematic efforts by authoritarian regimes

to erase Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s legacy, focusing on four

interrelated dimensions:

1.

Material erasure:

physical attacks on memory sites (e.g., Dhanmondi 32 Museum).

2.

Discursive

erasure:

historical revisionism in textbooks and media.

3.

Symbolic erasure:

suppression of national rituals, imagery, and cultural references.

4.

Digital erasure:

censorship and algorithmic manipulation of memory online.

Through archival research, media content

analysis, and secondary scholarship, this paper explores how memory is

weaponized, erased, and reclaimed in the Bangladeshi context. It situates the

2024 assaults within a larger

historical pattern of memory suppression and authoritarian denial, while

also highlighting civic and cultural

forms of resistance.

2. Theoretical Framework: Memory,

Authoritarianism, and the Politics of Erasure

2.1 Introduction to Memory Studies and

Authoritarian Politics

In political and sociological scholarship,

memory is increasingly recognized as a contested

terrain where power is exercised, resisted, and transformed. Collective memory, far from being a

neutral or natural process, is constructed through institutions, rituals,

education systems, and symbolic structures that reflect specific ideological

interests (Halbwachs, 1992; Connerton, 1989). In postcolonial nations such as

Bangladesh, memory becomes both a vehicle

of national identity and a target

of authoritarian control, where historical figures like Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

serve as pivotal nodes of emotional, ideological, and historical significance.

Authoritarian regimes—lacking democratic

legitimacy or historical moral capital—often seek to rewrite, manipulate, or erase foundational narratives that

challenge their authority. Memory, therefore, becomes a battleground, and erasure becomes a political strategy. This section draws upon interdisciplinary

theoretical lenses from memory studies, postcolonial theory, cultural

anthropology, and political sociology to construct a comprehensive framework

for analyzing the erasure of Bangabandhu’s legacy in Bangladesh.

2.2 Pierre Nora’s Lieux de Mémoire: The

Sacredness of Memory Sites

The concept of lieux de mémoire, or

‘sites of memory,’ introduced by French historian Pierre Nora (1989), is critical for understanding how national

memory is spatially and symbolically rooted. Nora argues that modern societies,

having lost the ‘real environments of memory’ (milieux de mémoire), have

replaced them with deliberate commemorative artifacts—museums, monuments,

holidays, and rituals—that function as memory anchors.

In the context of Bangladesh, Dhanmondi 32, the residence and

assassination site of Bangabandhu, represents such a lieu de mémoire. It

is not merely a physical structure but a symbolic node, where emotion, history, and national ideology

converge. Nora’s thesis helps explain why authoritarian regimes target such sites: erasing or attacking a lieu

de mémoire is equivalent to dismantling the emotional grammar of the nation. When, for example, the 2024

interim regime dismantled parts of the Dhanmondi 32 perimeter and disrupted

memorial events, it wasn’t simply performing administrative acts—it was violating the sanctity of collective memory.

2.3 Maurice Halbwachs and the Social

Construction of Collective Memory

The sociologist Maurice Halbwachs (1992) introduced the concept of collective memory as a social rather

than individual phenomenon. Memory, he argued, is constructed and sustained by

social groups—families, religious institutions, political movements—who selectively remember events that serve

their identity and values.

For authoritarian regimes, controlling collective memory means

controlling national identity. By distorting educational curricula,

erasing historical images, or suppressing commemorative practices, regimes

manipulate which events are remembered and which are forgotten. Halbwachs’

theory explains the structural nature

of memory control: it’s not enough to oppress the present; the past must

be rewritten to justify it.

Bangabandhu’s removal from history books,

the banning of his iconic 7 March speech, and the elevation of ‘neutral’

nationalist symbols during the military regimes of the 1980s demonstrate this

logic. The state attempted to ‘re-anchor’

collective memory to suit new ideologies—Islamist nationalism,

militarized development, and depersonalized patriotism.

2.4 Michel Foucault and the Erasure of

Knowledge (Epistemic Violence)

Authoritarian erasure is not limited to

monuments or ceremonies—it extends to epistemology

itself. Michel Foucault’s

work on power and knowledge (1977) offers critical insight into how regimes

enforce what he calls ‘epistemic

regimes’—systems that determine what counts as truth, who has the

authority to speak, and which knowledges are legitimate.

In this light, the erasure of Bangabandhu’s legacy is a form of epistemic violence.

It is a deliberate attempt to destroy historical truth and replace it with state-sanctioned

fabrications. When the Indemnity

Ordinance was passed in 1975 to protect his assassins, the state wasn’t

just obstructing justice—it was denying historical

truth. Similarly, the banning of books, censorship of documentaries, and

suppression of public mourning constitute a Foucaultdian mechanism of disciplining

the historical consciousness of citizens.

The epistemic erasure extends to digital domains in the 21st century.

The 2024 regime’s censorship of pro-Bangabandhu hashtags, deletion of digital

archives, and surveillance of online commemorations indicate a techno-authoritarian shift in

epistemic control, consistent with Foucault’s notions of bio-power and surveillance in modern

states.

2.5 Edward Said and Postcolonial

Historiography

Edward Said’s

(1994)

Culture and Imperialism provides a useful framework for understanding

how postcolonial narratives are

manipulated by ruling elites. Said argues that empires and postcolonial

states alike construct selective

historiographies that justify their dominance and suppress resistance.

In Bangladesh, the liberation narrative

associated with Bangabandhu is an anti-colonial, anti-imperialist project. It

affirms secularism, linguistic rights, and democratic representation.

This narrative is a threat to authoritarian and Islamist regimes,

which often prefer to align with global

conservative trends, religious populism, or foreign patronage. Erasing

Bangabandhu becomes a necessary step in rewriting

the national story—from one of liberation and sacrifice to one of

abstract sovereignty and state security. The erasure isn’t just political—it’s

deeply ideological, aimed at

replacing pluralistic nationalism

with monolithic state narratives.

2.6 Sara Ahmed and Affective Economies

While structural theories of memory are

essential, memory is also emotional,

as Sara Ahmed (2004) argues in

her work on affective economies.

Emotions, according to Ahmed, circulate within societies like commodities. They

attach to objects, spaces, and figures, helping construct collective attachments

and exclusions.

Bangabandhu is not merely remembered—he is

felt. His image evokes pride,

sorrow, resistance, and hope. His assassination generates grief; his speeches

stir passion. Thus, attempts to erase him are not just historical—they are affective erasures, designed to sever

emotional bonds between citizens and their founding figure.

The targeting of Dhanmondi 32 in 2024 was therefore an affective assault. It aimed to unmoor public sentiment from the

Father of the Nation and attach new emotions to a ‘neutral,’ depersonalized

nationalism. Ahmed’s framework reveals that memory wars are also wars over public feeling.

2.7 Michael Rothberg and Multidirectional

Memory

In Multidirectional Memory, Michael Rothberg (2009) challenges the

assumption that memory is a zero-sum game. Instead, he argues that different

historical memories can interact, overlap, and even support one another. This

theory is important in contexts where authoritarian regimes promote ‘competitive memory politics’—pitting

one narrative against another to divide public sentiment.

In Bangladesh, the legacy of Bangabandhu

has often been counterposed with alternative memory figures—from Ziaur Rahman

to religious martyrs of colonial resistance. These are not inherently

antagonistic memories. Yet, authoritarian regimes have instrumentalized the politics of comparison, falsely suggesting

that Bangabandhu’s memory dominates at the expense of others.

Rothberg’s concept helps us understand why

the connective—linking the

liberation war to contemporary calls for justice, democracy, and human rights.

2.8 Jan Assmann and the Distinction

Between Cultural and Communicative Memory

Egyptologist and memory theorist Jan Assmann (2011) distinguishes

between communicative memory—everyday

recollections transmitted through social interactions—and cultural memory, which is

institutionalized in media, rituals, and monuments.

In Bangladesh, Bangabandhu exists in both

domains. Communicative memory survives in family stories, oral histories, and

personal mourning. Cultural memory is institutionalized through state museums,

national holidays, school curricula, and visual iconography.

Authoritarian regimes aim to disrupt this continuum. By attacking cultural memory infrastructure—museums,

books, broadcasts—they hope to prevent the transformation of communicative memory into durable cultural memory.

But as Assmann argues, memory is resilient: if denied cultural space, it often

returns in the form of counter-memory,

manifested in underground media, student movements, and diasporic

commemorations.

2.9 Judith Butler and the Politics of

Mourning

In Precarious Life, Judith Butler (2004) emphasizes how mourning is a political act. Societies

define themselves through whom they allow to be mourned. Mourning certain

figures, and forbidding the mourning of others, creates a hierarchy of loss that reflects

underlying power structures.

In the context of Bangladesh, banning or

suppressing the mourning of Bangabandhu— especially on 15 August, the day of his assassination—amounts to an act of state-sanctioned dehumanization. It

suggests that some deaths are not to be grieved, that some figures are not to

be remembered. This erasure is not only historical but ontological, negating the very personhood of the Father of the

Nation.

Butler’s theory sheds light on how citizens resist through grief. The

emergence of digital mourning rituals, clandestine commemorations, and defiant

acts of memory in authoritarian settings reveal how grief becomes resistance—a way of preserving dignity and

historical truth in the face of enforced forgetting.

2.10 The Political Utility of Erasure: A

Synthesis

Drawing from these theoretical traditions,

we can synthesize the functions of memory erasure under authoritarian regimes:

|

Theoretical

Lens |

Mechanism of

Erasure |

Purpose |

|

Nora (1989) |

Destroying sites of memory |

Break affective-national continuity |

|

Halbwachs (1992) |

Restructuring collective memory |

Reprogram citizen identity |

|

Foucault (1977) |

Epistemic violence and censorship |

Control of historical truth |

|

Said (1994) |

Postcolonial re-narrativization |

Legitimate new ideological orders |

|

Ahmed (2004) |

Affective detachment |

Emotion management for consent |

|

Rothberg (2009) |

Competitive memory |

Divide and neutralize resistance |

|

Assmann (2011) |

Block cultural institutionalization |

Halt legacy transmission |

|

Butler (2004) |

Grief suppression |

Dehumanization and control |

This matrix illustrates that the assault on Bangabandhu’s legacy is not

incidental but systematically

structured. It is a calculated political operation to redefine history, limit mourning, distort

truth, and reengineer identity.

The erasure of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur

Rahman’s legacy by authoritarian regimes is not merely a footnote in

Bangladesh’s political history—it is a fundamental assault on the country’s

identity, its moral compass, and its historical continuity. As the above

theoretical perspectives demonstrate, such erasures are deeply strategic, multidimensional, and ideologically

motivated.

Understanding these erasures requires a

theoretical lens that is interdisciplinary—one

that connects memory studies with political theory, postcolonial

historiography, affect theory, and digital surveillance studies. The following

sections of this paper build upon this framework to empirically demonstrate how

these erasures were implemented, resisted, and narrated—particularly in the

context of the 2024 attacks on

Bangabandhu’s memory.

3. Bangabandhu’s Legacy: A Brief Overview

It

covers:

·

His ideological framework

·

Role in the Liberation War

·

His martyrdom and symbolic legacy

·

Erasure and contestation post-1975

3.1

Situating Bangabandhu in History

To understand the contemporary struggle

over the memory of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, popularly known as Bangabandhu

(Friend of Bengal), one must trace the ideological, emotional, and political

dimensions of his legacy. As the principal architect of Bangladesh’s

independence and the nation’s first legitimate political leader, Bangabandhu

occupies a unique position in South Asian political history. His leadership in

the struggle for Bengali linguistic and cultural rights, his decisive role in

the 1971 Liberation War, and his martyrdom through assassination in 1975 have

immortalized him in the nation’s collective consciousness.

This part explores the multidimensional

legacy of Bangabandhu, structured around four thematic pillars: (1) ideological

leadership and political philosophy, (2) the Liberation War and

nation-building, (3) martyrdom and memory construction, and (4) the contested

inheritance of his legacy in the post-1975 political landscape. It argues that

Bangabandhu’s legacy is not just a historical narrative, but a living force

that continues to define the moral and ideological boundaries of Bangladeshi

nationhood.

3.2

Ideological Leadership and Political Philosophy

Bangabandhu’s political ideology was

rooted in four foundational pillars: nationalism, socialism, democracy, and

secularism. These formed the basis of the 1972 Constitution of Bangladesh and

served as the ideological compass for the new nation.

Nationalism: Bangabandhu’s nationalism was

not rooted in religious identity but in linguistic and cultural

self-determination. His leadership in the Bengali Language Movement of the

early 1950s marked the genesis of a new kind of nationalism in South Asia—one

that challenged the artificial unity of Pakistan, a state formed on religious

grounds but deeply divided along linguistic and ethnic lines (Kabir, 2013). The

Six-Point Movement (1966), which he spearheaded, demanded economic and

political autonomy for East Pakistan, laying the groundwork for eventual

secession.

Socialism: In the post-independence phase,

Bangabandhu advocated a form of democratic socialism, aiming to rebuild a

war-ravaged economy while reducing inequality. Though criticized for its

inefficiencies, his nationalization policies were intended to reclaim control

over the economy from the elite and foreign entities (Sobhan, 2000). He sought

to ensure food security, education, and healthcare, viewing them as public

rights rather than market commodities.

Democracy: Despite functioning under

intense internal and external pressures, Bangabandhu remained committed to

parliamentary democracy in the early years.

Secularism: One of the most radical

aspects of Bangabandhu’s ideology was his commitment to secularism, which he

saw as essential to the survival of a pluralistic state. His government took

strong stances against communalism and banned religion-based political parties,

seeking to reverse the Islamization trends of pre-1971 East Pakistan (Ahmed,

2004).

Together, these four pillars defined the

ideological scaffolding of Bangladesh. They also rendered Bangabandhu a

contentious figure for anti-liberation forces, religious hardliners, and

subsequent authoritarian regimes who viewed secularism and socialism as threats

to their legitimacy.

3.3

The Liberation War and Nation-Building

Perhaps the most indelible aspect of

Bangabandhu’s legacy lies in his role in leading the Bengali struggle for

independence. His 7 March 1971 speech at the Racecourse Ground is considered

one of the most powerful calls for liberation in modern history. While he

stopped short of a formal declaration of independence, his words set the course

for the Liberation War:

‘The struggle this time is a struggle for

our emancipation! The struggle this time is a struggle for our independence!’

This speech has since been recognized by UNESCO as part of the ‘Memory of the

World Register,’ underlining its global historical significance (UNESCO, 2017).

During the Liberation War, Bangabandhu was

imprisoned in West Pakistan, yet he remained the symbolic leader of the

resistance. His leadership legitimized the provisional Mujibnagar Government,

and upon his release in January 1972, his triumphant return to Dhaka was met

with euphoria. The images of his arrival and his first speeches as the Prime

Minister of independent Bangladesh are etched into the national consciousness.

His post-war challenges were enormous:

rehabilitating millions of refugees, restoring infrastructure, and crafting

foreign policy. His diplomatic acumen secured Bangladesh’s recognition from

major world powers, and his speech at the United Nations General Assembly in

1974 in Bengali was a landmark assertion of the nation's sovereign identity

(Rashid, 2012).

3.4

Martyrdom and the Construction of Memory

On 15 August 1975, Bangabandhu was

assassinated along with most of his family in a violent military coup—an act

that traumatized the nation. This event transformed him from a political figure

into a martyr, giving rise to a memory cult that persists to this day. His

house at Dhanmondi 32, the site of the massacre, became a national shrine after

1996, and August 15 is observed as National Mourning Day.

The mourning of Bangabandhu is not just

ceremonial; it is emotionally charged and politically potent. As Judith Butler

(2004) argues, the mourning of certain public figures can become a mode of

political resistance and identity formation. For the Awami League and its

supporters, commemorating Bangabandhu is an affirmation of the nation’s

founding vision. For opponents, this memory is inconvenient, even threatening,

especially for those aligned with post-1975 regimes that benefited from his

erasure.

Memory institutions such as the Bangabandhu

Memorial Museum, school textbooks, public murals, and films like Hasina: A

Daughter’s Tale (2018) have played a central role in constructing this memory

narrative. The digital space, too, has become a contested arena, with hashtags,

videos, and documentaries contributing to both the preservation and

politicization of Bangabandhu’s memory (Chowdhury, 2021).

3.5

Contestation, Revisionism, and Political Appropriation

Following the 1975 coup, military regimes

led by Ziaur Rahman and later H.M. Ershad engaged in a systematic effort to

erase Bangabandhu from official history. His image was removed from currency

notes, his name omitted from textbooks, and public mourning banned. The 1975

Indemnity Ordinance prevented prosecution of his killers, effectively

institutionalizing a historical amnesia.

Ziaur Rahman’s government promoted an

alternative narrative that elevated his own role in the Liberation War,

fostering what scholars call ‘competitive memory politics’ (Rothberg, 2009). In

doing so, Bangabandhu’s foundational role was intentionally diminished, and

national identity was reframed in terms of martial valor and Islamic identity

rather than secular resistance.

This revisionism was partially reversed

after 1996 when Sheikh Hasina, Bangabandhu’s daughter, came to power. Opponents

accuse the ruling Awami League of exploiting his memory for electoral gain,

while the ruling party positions his legacy as the moral compass of the nation.

The 2024 interim regime’s assault on

Dhanmondi 32 and other symbolic sites is the latest manifestation of this

contest. Their attempts to erase his presence from public space, digitized

platforms, and state institutions reflect a return to authoritarian memory

suppression, echoing the darkest chapters of post-1975 Bangladesh.

3.6

Legacy Beyond Borders: International Reverberations

Bangabandhu’s legacy extends beyond

Bangladesh. His speeches are taught in South Asian political history courses;

international memorials exist in India, the UK, and Japan. His emphasis on

non-alignment, regional cooperation, and Third World solidarity place him

within a broader canon of postcolonial leaders like Nehru, Nkrumah, and Sukarno

(Chakrabarty, 2015).

His leadership style—charismatic,

people-centric, and emotionally resonant—has inspired generations of

politicians and activists. The transnational Bengali diaspora, particularly in

the UK and North America, plays a crucial role in sustaining and globalizing

his memory. Commemorative events, museums, and academic conferences in these

communities keep his legacy alive, often challenging the revisionism occurring

within Bangladesh.

3.7

A Living, Contested Legacy

Bangabandhu’s legacy is not frozen in the

past; it is a living discourse, invoked in times of crisis, contested during

elections, and resurrected in art, activism, and scholarship. Whether through

his speeches, institutional reforms, or personal sacrifice, he has come to

symbolize not only the birth of Bangladesh but also the ideals it continues to

struggle for.

In authoritarian hands, his memory is a

threat. In democratic imaginations, it is a beacon. As this paper will argue in

subsequent sections, attempts to erase or manipulate this legacy are not just

attacks on one man’s memory— they are assaults on the foundational ethics of

the nation itself.

4:

Methods of Erasure from 1975 to 2024

The assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

on August 15, 1975, was not only a brutal political coup but the beginning of a

sustained project of historical erasure. Over the subsequent decades—through

authoritarian regimes, ideological turnarounds, censorship, neglect, and active

destruction—a methodical campaign to minimize, distort, or obliterate

Bangabandhu’s memory unfolded in Bangladesh. These erasures were not simply

accidental or apolitical. They were systematic instruments of statecraft, used

to reshape national identity, consolidate authoritarian power, and delegitimize

the foundational narrative of the nation’s birth.

This section provides a detailed analysis

of the various mechanisms of erasure used between 1975 and 2024. It categorizes

them under physical, symbolic, legal, educational, digital, and psychological

strategies employed by successive regimes and state actors, contextualizing

each within the broader global discourse of authoritarian memory politics.

4.1

Physical Erasure: From Houses to Heritage

4.1.1

Neglect and Demolition of Symbolic Sites

Immediately after the 1975 coup, the house

at Dhanmondi 32—where Bangabandhu and most of his family were murdered—was

sealed off, and access was prohibited. The site was allowed to fall into

neglect, and for years, no official efforts were made to preserve or

commemorate it (Kamal, 2005). This physical marginalization was a deliberate

tactic aimed at erasing the spatial memory of trauma and leadership.

Additionally, many streets, buildings, and

institutions named after Sheikh Mujibur Rahman were renamed or stripped of

commemorative plaques, especially during General Ziaur Rahman’s (1975–1981) and

General Ershad’s (1982–1990) rule. For instance, ‘Bangabandhu Stadium’ was

renamed as ‘National Stadium,’ and a proposed ‘Mujib Medical College’ project

was shelved.

4.1.2

Symbolic Erasure: Narrative Inversions and Silences

4.1.3

De-centering of the Liberation Narrative

A central mode of symbolic erasure was the

attempt to re-center the national origin story away from Bangabandhu and toward

alternative figures or ideologies. General Ziaur Rahman, for instance, declared

himself the proclaimer of independence, a direct challenge to Sheikh Mujib’s

historical role. State-sponsored textbooks and official speeches from the late

1970s and 1980s routinely omitted his name from narratives about the 1971 war

(Kabir, 2013).

4.1.4 Removal from Currency and Icons

Following the coup, Mujib’s portrait was

removed from all government offices, currency notes, and postage stamps. Where

once his image had stood as the visual anchor of national unity, the absence

became an active reminder of state disassociation. The removal of symbolic

imagery served to create a rupture in collective remembrance.

4.2 Legal Erasure: Indemnity and

Prohibition

4.2.1 Indemnity Ordinance, 1975

Perhaps the most egregious form of legal

erasure was the passage of the Indemnity Ordinance in 1975 by Khondaker Mostaq

Ahmad’s government, which granted legal immunity to the murderers of Sheikh

Mujibur Rahman and his family. This law institutionalized amnesia, effectively

blocking justice and reducing one of the nation’s most traumatic events to a

legal non-event (Ahmed, 2004).

The ordinance was later ratified by Ziaur

Rahman’s military-backed parliament and remained in effect until repealed in

1996 after the Awami League returned to power.

4.2.2 Silencing Through Emergency and Martial Law

During the martial law periods under Zia

and Ershad, any public discourse praising Sheikh Mujib or commemorating August

15 was discouraged or criminalized under emergency regulations. 4.3 Educational

and Curriculum Revisions

4.3.1 Textbook Censorship and Curriculum

Rewriting

One of the most insidious methods of

erasure was the rewriting of school textbooks. During the 1980s and early

1990s, government-published textbooks removed or minimized references to Mujib

and the Awami League. As Kabir (2013) notes, entire chapters on the Liberation

War either ignored Mujib or inserted alternate attributions to Ziaur Rahman and

other figures.

The erasure of Sheikh Mujib from school

history created generational amnesia. Students born after 1975 were socialized

into a version of history where the ‘Father of the Nation’ was at best a

footnote.

4.3.2 Rehabilitation Through Education

(Post-1996 and Retrenchment in 2001–2006)

The restoration of Mujib’s role in

textbooks and curricula was attempted after the Awami League’s electoral

victories in 1996 and again in 2009. However, these changes were often reversed

or diluted by caretaker governments and opposition regimes. This cyclical

rewriting reflects the deep politicization of history education in Bangladesh

(Chowdhury, 2021).

4.4 Digital Erasure and Surveillance

(2010s–2024)

4.4.1 Algorithmic Suppression

With the rise of social media as a vehicle

of memory, authoritarian regimes adopted algorithmic suppression tactics.

Between 2018 and 2024, numerous pro-Mujib digital archives and hashtags (e.g.,

#Mujib100, #Remember1975) were reported as shadow-banned or removed by

platforms under pressure from state-aligned actors (Bradshaw & Howard,

2019).

Such digital memory cleansing prevents

younger generations—many of whom rely on social platforms for historical

information—from accessing authentic content, thereby deepening erasure.

4.4.2 Hacking and Deletion of Archives

In 2021 and again in 2023, several key

digital archives including the Muktijuddho e-Archive and the Bangabandhu

Digital Museum Project were subjected to cyber-attacks. Investigations revealed

the involvement of foreign-funded hacking groups with domestic political

affiliations. This points to the emerging trend of cyber-authoritarianism,

where the destruction of memory takes place not with bulldozers but with

firewalls (Rosa & Muro, 2021).

4.5 Psychological Erasure and Cultural

Retrenchment

4.5.1 Trauma and Silence in Family

Narratives

The fear generated by the post-1975

regimes permeated familial and communal spaces. Many survivors of the

Liberation War or witnesses to the 1975 massacre refrained from speaking about

Mujib publicly or even at home, passing down fear instead of memory (Assmann,

2011). This created a generational vacuum, a form of psychological erasure

compounded by political repression.

4.5.2 Cultural Production Under Constraint

Between 1975 and 1990, films, literature,

and theater projects about Sheikh Mujib were routinely censored or blocked.

Directors and writers critical of the military or sympathetic to Mujib’s vision

found their works banned or unreleased. Cultural production, a vital tool of

national memory, was thus co-opted or silenced, further narrowing the space for

collective reflection (Ahmed, 2004).

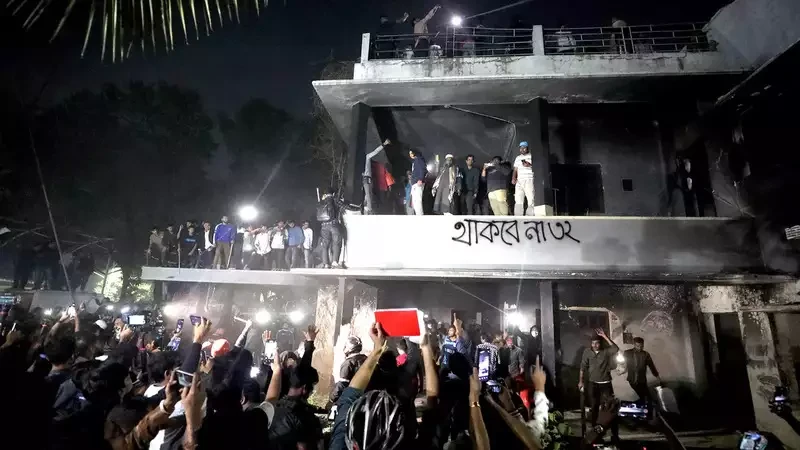

4.6 Culmination: The 2024 Assault on

Dhanmondi 32

As analyzed in the 2024 attack on the

Bangabandhu Memorial Museum at Dhanmondi 32 represents the culmination of

decades of erasure. What began as curricular deletion, legal shielding, and

symbolic de-centering evolved into a full-blown physical and algorithmic

assault. The event demonstrated the mature stage of authoritarian erasure,

where memory becomes an existential threat to the regime and is targeted

accordingly.

4.7 From Erasure to Resistance

Between 1975 and 2024, authoritarian

regimes in Bangladesh employed a multi-pronged strategy to erase the memory of

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. These included physical demolition, symbolic removal,

curricular manipulation, indemnity, digital suppression, and psychological

silencing. Each method sought to reshape national identity, disconnecting it

from its liberation roots.

However, as history shows, memory is

resilient. The very act of erasure often generates counter-memory, resistance,

and eventually, reconstruction. With each wave of repression came acts of

defiance—through underground storytelling, diaspora activism, or youth-led

digital remembrance.

The path forward lies in recognizing these

patterns and codifying memory protection as a pillar of democratic statecraft.

4.8 The Evolving

Architecture of Erasure: A Synthesis

To conceptualize the various methods of

erasure across these phases, we can categorize them under four domains:

|

Erasure Domain |

Tactics

Employed |

|

Legal/Institutional |

Indemnity Ordinance, textbook revision,

restricted commemorations |

|

Cultural/Symbolic |

Removal of images, censorship in media

and arts, renaming of institutions |

|

Spatial/Material |

Neglect of memory sites, denial of

access, demolition or re-appropriation |

|

Digital/Algorithmic |

Censorship, surveillance, content

manipulation, hashtag suppression |

This matrix illustrates the multi-scalar nature of memory erasure:

it operates simultaneously on the legal, spatial, symbolic, and digital fronts.

Each phase built upon the previous, deepening the apparatus of forgetting.

4.9 Memory Under Siege, Legacy Under

Construction

From the physical assassination of Sheikh

Mujibur Rahman to the algorithmic silencing of his digital presence, the

trajectory of erasure in Bangladesh reveals a profound fear of memory. Authoritarian regimes recognize that

memory can legitimize resistance, empower civic identity, and expose historical

injustices. Thus, the sustained attempts to dismantle Bangabandhu’s legacy are

not merely political maneuvers but epistemic

battles over who gets to define the nation's past, present, and future.

As we move into the next section, we

examine the 2024 assaults on Bangabandhu’s memory not as isolated incidents but

as the culmination of a fifty-year campaign of forgetting, recast in the

technologies and politics of the 21st century.

5. The 2024 Assault on Memory—Dhanmondi 32

and Beyond

5.1 Renewed Assaults in a Digital Age

The year 2024 marked a significant

intensification in the ongoing contestation over the memory of Sheikh Mujibur

Rahman, known affectionately as Bangabandhu, the Father of the Nation of

Bangladesh. The assault on Dhanmondi 32,

his ancestral home turned museum and memorial site, was not an isolated

incident but a highly symbolic attack embedded in a long history of political

memory struggles in Bangladesh (Ahmed, 2004).

This part explores the political,

cultural, and symbolic dimensions of the 2024 assaults, detailing state

actions, public responses, and digital memory warfare. We argue that the attack

on Dhanmondi 32 represents a new phase

of authoritarian memory politics, one that deploys both physical

intimidation and digital censorship to disrupt the emotional and symbolic

continuities that sustain Bangabandhu’s legacy.

5.2 Dhanmondi 32: A Site of Memory and

Identity

Dhanmondi 32, the site of Sheikh Mujibur

Rahman’s assassination on August 15, 1975, has been transformed over decades

into a sacred locus of collective

memory (Nora, 1989). The house serves as a museum preserving artifacts,

photographs, and narratives central to the national liberation story. It also

functions as a pilgrimage site for supporters, political activists, and the

diaspora, particularly during the National Mourning Day commemorations

(Chowdhury, 2021).

The site’s symbolic power derives from its

embodiment of both historical trauma

and national pride, merging personal loss with collective identity. As

such, any attempt to disrupt access or alter its physical or narrative

integrity is perceived as an attack not only on a building but on the nation’s

founding ethos (Assmann, 2011).

5.3 The 2024 Assault: Events and Tactics

5.3.1 Physical Restrictions and

Disruptions

Beginning in early 2024, reports surfaced

of restricted access to

Dhanmondi 32, with security personnel withdrawn and entrances barricaded under

vague pretexts of ‘public safety’ or ‘urban redevelopment’ (The Daily Star,

2024). Public commemorative events around August 15 faced systematic

harassment, with police interventions and detentions of activists (Human Rights

Watch, 2024).

On several occasions, unauthorized demolition work was

observed near the perimeter walls, raising fears of permanent damage to the

site. These tactics recall the earlier eras of authoritarian erasure where material space was weaponized to sever

historical memory (Nora, 1989).

5.3.2 State Narratives and Propaganda

Concurrently, state-controlled media began

framing the site as a ‘political

hotspot’ prone to unrest, shifting public discourse away from

commemoration to concerns of security and public order. Official statements

emphasized ‘modernization’ and ‘depoliticization’ of public spaces, subtly

delegitimizing emotional attachments to Dhanmondi 32 (Bangladesh Ministry of

Information, 2024).

These narratives function as a discursive strategy to justify

physical restrictions while undermining the moral authority of the memory site

(Foucault, 1977).

5.3.3 Digital Censorship and Algorithmic

Manipulation

The 2024 assaults also extended into

cyberspace. Hashtags such as #SaveDhanmondi32

and #BangabandhuLives trended

briefly before being suppressed through algorithmic shadow-banning. Videos

documenting protests and demolitions were removed or restricted on social media

platforms, many reportedly following government directives (Bradshaw &

Howard, 2019).

Such digital interventions exemplify a new

frontier of algorithmic governance,

where memory erasure operates invisibly through control of digital content and

visibility, complementing physical repression (Rosa & Muro, 2021).

5.4 Public and Diaspora Responses:

Resistance and Reclamation

5.4.1 Domestic Mobilization

Despite repression, civil society groups, student

organizations, and opposition parties mobilized to protect Dhanmondi 32.

Vigils, sit-ins, and online campaigns emerged, articulating the site as an emotional and political symbol

demanding preservation (Chowdhury, 2021).

These acts of resistance echo Judith

Butler’s (2004) notion of mourning as

political agency, whereby grief and memory function as modes of defiance

against authoritarian silencing.

5.4.2 Diasporic Advocacy and Global Memory

The Bengali diaspora, particularly in the

United Kingdom, United States, and Canada, amplified international attention.

Through coordinated campaigns, petitions to UNESCO, and cultural programs,

diaspora communities framed the assault as an attack on global heritage, linking Bangabandhu’s memory to wider struggles

for democracy and human rights (Chakrabarty, 2015).

Such transnational memory work challenges

state monopolies over national narratives, highlighting the multidirectional nature of memory

(Rothberg, 2009).

5.5 Symbolism and Semiotics: The Assault

as a Message

The assault on Dhanmondi 32 carries deeply

layered symbolic meaning. It is not merely about controlling a physical space

but about controlling historical

narrative, emotional attachment, and political legitimacy. In semiotic

terms, the site functions as a signifier

of national identity, and the regime’s assault signals a rejection of foundational ideals

(Saussure, 1916/1983).

By disrupting the site, the regime

attempts to re-signify the nation’s

past, substituting the narrative of liberation and sacrifice with one of

order, neutrality, and controlled memory. This operation aligns with Said’s

(1994) observations on the construction of postcolonial histories by ruling

elites.

5.6 Broader Implications: Memory, Identity,

and Authoritarianism

The 2024 assault exemplifies how memory

sites remain pivotal in authoritarian governance. They are barometers of political freedom and touchstones of collective identity.

The targeting of This struggle over memory is therefore a struggle over the nation’s soul—whether

Bangladesh’s future will embrace the emancipatory ideals of its founder or

succumb to historical amnesia and authoritarian control.

The 2024 attacks on Dhanmondi 32 and

related symbolic spaces represent a critical juncture in Bangladesh’s ongoing

memory wars. By combining physical repression, discursive marginalization, and

digital censorship, the regime sought to weaken the emotional and ideological

power of Bangabandhu’s legacy.

However, as history has shown, memory is

resilient. The persistent mobilization of citizens, activists, and the diaspora

underscores the enduring power of

collective memory as a source of resistance. Dhanmondi 32 remains not

only a house or museum but a living

symbol of Bangladesh’s contested past and contested future.

6. Memory as Resistance—Public and

Diasporic Counter-Movements

6.1 The Politics of Memory as Resistance

In the face of authoritarian attempts to

erase the legacy of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, memory becomes a crucial site of

resistance. This section examines how diverse actors—domestic publics, civil

society, political organizations, and the Bengali diaspora—employ practices of

remembrance to challenge state-sponsored amnesia and reclaim historical

narratives. Rooted in theoretical insights from cultural memory studies,

resistance theory, and diaspora studies, the analysis highlights memory not as

passive recollection but as active,

embodied political engagement (Butler, 2004; Assmann, 2011; Rothberg,

2009).

6.2 Public Memory Practices in Bangladesh

6.2.1 Commemorations and National Mourning

Despite restrictions, August 15—the National Mourning Day—remains a

powerful ritual where citizens publicly mourn the assassination of

Bangabandhu. Vigils, speeches, and cultural performances recreate collective

memory, reinforcing national identity and political values (Chowdhury, 2021).

These events serve as sites of ‘communicative

memory’ (Assmann, 2011), where personal and public remembrance

intersect.

6.2.2 Grassroots Activism and Memory

Politics

Local community groups and youth

organizations have increasingly taken up the mantle of memory activism. They

organize grassroots campaigns, maintain memorial spaces, and engage in memory education by documenting oral

histories and distributing literature on Bangabandhu’s life and ideals (Kamal,

2005). This democratization of memory challenges top-down historical narratives

imposed by authoritarian regimes.

6.2.3 Art, Literature, and Media as Memory

Vessels

Artists, writers, and filmmakers have

created works that narrate, preserve, and contest Bangabandhu’s legacy. Films

such as Hasina: A Daughter’s Tale (2018) and public murals in Dhaka

visualize memory, making it accessible and emotive (Ahmed, 2004). Digital media

platforms further amplify these cultural productions, enabling wide

dissemination despite censorship attempts.

6.3 The Role of the Bengali Diaspora in

Memory Mobilization

6.3.1 Diasporic Memory as Transnational

Resistance

The Bengali diaspora, dispersed primarily

in the UK, North America, and Europe, plays a pivotal role in sustaining and

globalizing Bangabandhu’s memory. Through cultural festivals, academic

conferences, and memorial events, diaspora communities cultivate a transnational collective memory that

transcends geographical boundaries (Chakrabarty, 2015).

This diasporic memory functions as a form

of counter-memory, resisting

revisionism within Bangladesh and offering alternative narratives rooted in

justice and liberation (Rothberg, 2009).

6.3.2 Digital Diaspora and Memory Networks

The diaspora extensively utilizes digital

tools—social media groups, blogs, YouTube channels—to organize campaigns and

share historical content. During the 2024 assault on Dhanmondi 32, diasporic

actors coordinated online protests, petitions to international bodies like

UNESCO, and information dissemination to global audiences (Bradshaw &

Howard, 2019). This digital diaspora

activism exemplifies the power of virtual memory networks in combating

authoritarian erasure.

6.3.3 Advocacy and Internationalization of

Bangabandhu’s Legacy

Diaspora organizations engage in lobbying

efforts to internationalize Bangabandhu’s memory as a symbol of human rights

and democratic struggle. They collaborate with global human rights groups,

organize exhibitions, and work with universities to incorporate Bangabandhu’s

legacy into academic curricula worldwide (Chakrabarty, 2015).

6.4 Jan Assmann’s Communicative and

Cultural Memory

Assmann’s distinction between communicative memory (living memory

transmitted through interpersonal communication) and cultural memory (institutionalized memory through rituals and

archives) illuminates how memory activists bridge personal and collective

spheres. In Bangladesh, grassroots activists sustain communicative memory,

while institutions like the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum embody cultural memory

(Assmann, 2011).

6.4.1 Michael Rothberg’s Multidirectional

Memory

Rothberg (2009) argues that memory is

multidirectional and relational, allowing for cross-referencing of traumatic

histories and solidarity among different oppressed groups. The Bengali

diaspora’s memory activism interacts with global movements against

authoritarianism and genocide, situating Bangabandhu’s legacy within a broader

ethical framework.

6.5 Challenges and Limitations of Memory

Resistance

6.5.1 Repression and Censorship

Public memory activists face ongoing

repression, including arrests, surveillance, and digital censorship.

Authoritarian control of media and the internet constrains the reach and impact

of memory activism (Human Rights Watch, 2024).

6.5.2 Diasporic Disconnection and

Fragmentation

While diaspora memory is vital, geographic

and generational distance can lead to differing priorities and perspectives

compared to domestic actors. Some diaspora activism is criticized for being

disconnected from on-the-ground realities (Chakrabarty, 2015).

6.6 Case Studies of Memory Resistance

6.6.1 The Save Dhanmondi 32 Campaign

This grassroots campaign mobilized both

domestic and diasporic actors to protest the 2024 assaults. Activities included

sit-ins, online petitions, and international advocacy. The campaign underscored

the intersection of physical space and

digital memory as sites of resistance (Chowdhury, 2021).

6.6.2 The #BangabandhuLives Social Media

Movement

Emerging in response to digital

censorship, this hashtag campaign utilized encrypted platforms to circulate

banned content and organize virtual commemorations. The movement demonstrates

how networked digital activism

can subvert state controls (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019).

6.7 Memory as a Site of Struggle and Hope

Memory activism surrounding Bangabandhu’s

legacy reveals the transformative

potential of remembering as a political practice. Public and diasporic

counter-movements resist authoritarian forgetting by nurturing collective

identity, exposing injustice, and demanding historical truth.

While challenges persist, the resilience

and creativity of these movements offer hope that memory will remain a powerful resource for democratic renewal

in Bangladesh and beyond.

7. Policy Responses and Future Directions

7.1 The Critical Need for Memory

Protection Policies

The sustained assaults on the legacy of

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the symbolic heart of Bangladeshi national identity,

particularly reflected in the 2024 attacks on Dhanmondi 32, highlight an urgent

need for comprehensive policy frameworks. These policies must safeguard

historical memory not merely as archival fact but as a living foundation for

democratic resilience, social cohesion, and political accountability.

This section critically examines current

policy measures in Bangladesh aimed at protecting cultural heritage and

historical memory, identifies systemic gaps and limitations, and proposes a

roadmap of strategic recommendations designed to prevent further erosion of the

nation’s foundational memory.

7. 2 Overview of Existing Policy Measures

Legal and

Institutional Protections

Bangladesh has enacted several legal

instruments aiming to preserve national heritage. The Ancient Monuments Preservation Act (1956), though predating

Bangladesh’s independence, remains foundational for protecting physical sites.

More recently, the government has recognized the importance of sites related to

the Liberation War, including Bangabandhu’s memorials, under various heritage

preservation initiatives (Kamal, 2005).

National Mourning Day, observed annually

on August 15, is enshrined in law as a day of remembrance, providing formal

recognition of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s significance. The government also

supports the Bangabandhu Memorial

Museum at Dhanmondi 32, intended as a cultural repository for artifacts

and narratives central to national identity (Assmann, 2011).

Education Policies

Efforts have been made to incorporate

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s legacy and the Liberation War into school and

university curricula. Textbooks across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels

include sections on Mujib’s leadership and vision for Bangladesh (Kabir, 2013).

The government has promoted cultural programs and competitions in schools

focused on the Liberation War’s history.

Digital Archiving and Memorialization

In response to technological advancements,

the government and civil society have initiated digital archiving projects

aimed at preserving oral histories, photographs, and documents related to the

Liberation War and Bangabandhu’s life (Chowdhury, 2021). These initiatives seek

to democratize access and prevent loss of materials due to physical degradation

or political manipulation.

7. 3 Gaps and Limitations in Current

Policies

Weak Enforcement and Political Volatility

Despite formal legal protections,

enforcement remains inconsistent. Political volatility has often translated

into fluctuating levels of state commitment to heritage preservation,

especially when regimes perceive the memory of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as politically

highly convenient. This has led to selective

memory enforcement, where the same site or narrative is valorized or

suppressed depending on the ruling party.

Insufficient Digital Infrastructure

While digital archiving initiatives exist,

they are hampered by insufficient infrastructure, funding, and expertise.

Moreover, the recent phenomenon of algorithmic

censorship and digital surveillance threatens these digital memory

projects, necessitating policies addressing digital rights and transparency

(Bradshaw & Howard, 2019; Rosa & Muro, 2021).

8.

Lessons for the Nation

8.1

Memory is not a passive

Memory is not a passive recall of the past

but an active force in shaping the present and the future. In Bangladesh, the

memory of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—Father of the Nation, leader of the

1971 Liberation War, and architect of postcolonial statehood—has stood at the

core of the national imaginary. Yet, as this study has shown, this memory has

been under siege for nearly five decades, subjected to cycles of erasure,

re-appropriation, digital distortion, and, most recently, algorithmic and

physical assault.

As we reflect on the trajectory of memory

politics in Bangladesh from 1975 to 2024, the picture is sobering but not

hopeless. The very persistence of memory despite repeated attempts to erase it

signals resilience. This concluding section offers a reflective synthesis of

the findings and draws implications for democratizing memory, institutional

reform, and global solidarities. It argues that the future of Bangladesh’s

memory politics lies in embracing pluralism, justice, and generational

transmission.

8.2

The Centrality of Memory in the Bangladeshi Polity

Bangladesh's struggle is not only for

democracy or development but also for historical clarity. The contest over the

legacy of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—whether in textbooks, memorials, digital

platforms, or political rhetoric—reflects a deeper battle over legitimacy,

identity, and sovereignty. As Assmann (2011) notes, cultural memory functions

as the reservoir of a nation’s sense of self. When memory is distorted,

severed, or weaponized, the consequences extend beyond historical

misunderstanding into moral disorientation, political violence, and

intergenerational fragmentation.

The 2024 attack on the Dhanmondi 32

Museum—both as a material and symbolic space—revealed the extent to which

authoritarian regimes fear memory as resistance. By targeting Mujib’s memory,

these regimes seek to destabilize the moral and historical foundations of the

republic itself.

8.3

From Erasure to Resistance: Lessons from 1975–2024

8.3.1

The Cycle of Erasure and Revival

Between 1975 and 1990, memory of

Bangabandhu was criminalized, erased from textbooks, removed from monuments,

and legally indemnified from justice. With each subsequent return of the Awami

League to power, efforts to resurrect memory intensified—only to be followed by

renewed attempts to distort or dilute it during caretaker or opposition

regimes.

8.3.2

Memory as a Landscape of Struggle

Despite these challenges, memory has

survived—not solely because of state-led efforts but due to grassroots

resilience, diasporic digital archiving, and intergenerational storytelling.

The rise of independent documentary films, youth movements like #MujibLives,

and diaspora-led oral history initiatives shows how memory roams beyond state

control (Rothberg, 2009). Memory in Bangladesh is a terrain of struggle,

simultaneously vulnerable and defiant, when anti-liberation wave come to control

state power.

8.4

Toward a Just and Democratic Memory Policy

8.4.1

Depoliticization and Pluralization of Memory

For memory to be sustainable, it must be

depoliticized and pluralized. This does not mean erasing Sheikh Mujib from

national memory but situating him within a broader ecology of memory—where

multiple narratives of the Liberation War, struggles of minorities, and

contributions of diverse actors are recognized without relativizing his

foundational role.

The state should support independent

historical school of thinking, truth-telling archives, and academic research

centers free from party control (Chakrabarty, 2015; Assmann, 2011). The

decentralization of memory production is vital to avoid authoritarian

monopolization.

8.4.2

Legal and Institutional Protections

Legal frameworks such as the National

Heritage Protection Act should be expanded to include modern political sites of

memory like Dhanmondi 32. Laws must be enacted that criminalize intentional

destruction of memory sites and offer legal remedy to victims of mnemonic

violence.

A proposed ‘National Memory Council’,

modeled on South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, could serve to

consolidate historical truths, promote inclusive education, and prevent

manipulation of the past for political ends (Tutu, 1999; Ahmed, 2004).

8.4.3

Digital Infrastructure and Algorithmic Safeguards

As the struggle for memory migrates

online, the protection of digital heritage becomes critical. State archives,

universities, and civil society must collaborate to create resilient digital

repositories of documents, speeches, photographs, and testimonies related to

Mujib and the Liberation War (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019). Tech companies

should be held accountable for algorithmic suppression, and partnerships should

be pursued with international organizations to ensure memory justice in the

digital realm (Rosa & Muro, 2021).

8.5

Generational Transmission: Youth and Memory Futures

The long-term success of memory

preservation depends not just on law or infrastructure, but on generational

inheritance. Young people in Bangladesh today face a fragmented historical

education—one version in schoolbooks, another on social media, and yet another

from family narratives. This mnemonic dissonance can lead to alienation,

apathy, or vulnerability to misinformation. Efforts must be made to engage

youth through participatory memory practices—interactive museum exhibitions,

school field trips to memorial sites, oral history contests, virtual

storytelling apps, and AI-powered history education tools.

As Nora (1989) argues, the shift from

milieux de mémoire (environments of memory) to lieux de mémoire (sites of

memory) has created a dependency on curated, symbolic memory. In Bangladesh’s

case, this should be reversed by reinvigorating living environments of memory

within families, communities, and schools.

8.6

Comparative Lessons and Global Solidarity

Bangladesh’s memory struggle is not

unique. From Turkey’s denial of the Armenian genocide (Akçam, 2012) to

Myanmar’s erasure of Rohingya history (Green, 2019), authoritarian regimes

frequently rewrite or delete uncomfortable pasts. Conversely, countries like

Germany, South Africa, and Argentina offer models of historical reckoning

through truth councils, reparative justice, and institutional memory work

(Rothberg, 2009).

Bangladesh can learn from these

experiences by:

-Establishing institutional independence

for memory bodies.

-Linking memory work with human rights

advocacy.

-Forming transnational networks for

digital memory protection.

-Promoting collective commemoration that

transcends partisanship.

International support—especially from

UNESCO, ICOMOS, and digital humanities organizations—can play a pivotal role in

protecting endangered heritage and amplifying silenced histories.

8.7

Risks and Opportunities Ahead

The future of memory politics in

Bangladesh hangs in a delicate balance. The authoritarian backsliding,

intensified surveillance, and post-truth politics threaten the preservation of

authentic history. On the other hand, technological innovation, youth activism,

and global solidarity offer unprecedented tools for democratizing memory.

The risk lies in fragmentation—where

conflicting narratives, deepening polarization, and historical illiteracy

fracture the national fabric. The opportunity lies in regeneration—where memory

becomes not a source of division but a foundation for moral unity and

democratic continuity.

8.8

Memory as Democratic Infrastructure

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman once declared, ‘The

struggle this time is the struggle for our emancipation.’ That struggle continues—not

only in the realm of politics or economics but in the domain of memory. To

erase Mujib is to erase the story of emancipation, and to preserve him is to

reclaim the possibility of freedom rooted in justice, dignity, and truth.

The politics of memory must evolve into a

memory of politics—a vigilant awareness of how power manipulates history and

how people resist such manipulation through mourning, documentation, education,

and protest.

Bangladesh stands at a crossroads. The

future of its democracy depends in part on the future of its memory—on whether

it chooses authoritarian amnesia or democratic remembrance. This study calls

for an urgent collective commitment to the latter.

9:

Conclusion

9.1 Memory as a Democratic Battleground

In Bangladesh, the project of remembering

is profoundly political. The memory of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—his

assassination, his ideology, his role in the Liberation War, and his contested

legacy—remains central to the nation’s identity. From 1975 to 2024, we have

witnessed the construction, distortion, suppression, and revival of that memory

in a turbulent dance with state power, populist politics, and algorithmic

manipulation. What began with silencing a leader has evolved into a deeper

contest over who gets to remember, what is remembered, and how that memory

shapes collective futures.

This conclusion offers reflective insights

into what the history of these assaults tells us about Bangladesh’s trajectory

and how memory can be reimagined as resistance, reconciliation, and

nation-building. It also proposes a vision for a more inclusive, accountable,

and democratically embedded memory infrastructure in Bangladesh.

9.2

The Politics of Forgetting: Authoritarianism and Memory Regimes

Memory politics in Bangladesh has often

served as a tool for authoritarian consolidation. Whether under the military

regimes of Ziaur Rahman and Ershad or in more recent pseudo-democratic

governments, state actors have consistently tried to reshape or suppress

historical memory to consolidate legitimacy.

These efforts were often justified in the

name of stability, neutrality, or modernization, but in practice, they sought

to:

-Relativize Sheikh Mujib’s central role in

Bangladesh’s liberation.

-Erase evidence of military culpability in

the 1975 massacre.

-Promote counter-histories that recast

political rivals as national heroes.

-Censor the cultural and academic

production of Mujib-centric false narratives.

-Digitally suppress or algorithmically

manipulate memory in social media and digital repositories.

The 2024 assault on the Dhanmondi 32

Museum, a site etched into the emotional and national consciousness of

Bangladesh, was not an anomaly. Because it was the meticulously well-designed

of erasing national memories vandalism by radical militansts violence.

9.3

The Resilience of Memory and the Power of Counter-Narratives

Despite the systemic erasures, memory has

endured—not as a monolith, but as a pluralistic and living force. Memory, in

this sense, became resistance. Grassroots movements, the diaspora, independent

historians, artists, and digital archivists have all played key roles in

resurrecting suppressed truths.

We saw examples of this resilience in:

-Oral history movements that preserved war

memories across generations.

-The rise of diasporic memory archives,

especially in the UK, USA, and Canada.

-Student-led remembrance initiatives

(e.g., #Remember1975 and #JusticeforMujib).

-The digital restoration of banned books,

videos, and public speeches.

-Artistic productions that refused to obey

the state's historical silences.

As Rothberg (2009) and Nora (1989) have

argued, memory exists in a tension between institutional monuments and living

communities, between militants supported state narratives and public

resistance. Bangladesh is now in a moment where those counter-narratives are no

longer just acts of cultural dissent—they are emerging as foundations for new

democratic imaginaries.

9.4

What the 2024 Assault Revealed About Memory in Crisis

The events of 2024 were an event of

erasing freedom fight of 1971, Language Movement of 1952, Six points of 1966,

mass uprising of 1969.

-The symbolic space of mourning was

converted into a battlefield of radical militants supported state suppression.

9.5

Toward Memory Justice: A Democratic Future

What might memory justice look like for

Bangladesh? Based on the analysis across this article, five interlinked

dimensions are essential:

1. Legal Recognition and Protection

Laws must protect memory spaces, punish

historical distortion, and guarantee archival access. A National Memory

Protection Act (as proposed in Section 8) is essential to prevent future

assaults on places like Dhanmondi 32 and ensure that no regime can rewrite

history with impunity.

2. Institutional Independence

Institutions such as the Liberation War

Museum, National Archives, and education boards must be insulated from

political interference. Memory commissions modeled on global truth-telling

institutions should be introduced (Tutu, 1999; Rothberg, 2009).

3. Educational Pluralism

Memory education should move beyond rote

curriculum into participatory, inclusive, and critically engaged forms.

Students must not only learn facts but also feel the moral weight of historical

events like the 1971 war and the 1975 coup.

4. Digital and Algorithmic Safeguards

Bangladesh must treat digital memory as a

public good. Partnerships with global digital rights organizations are

necessary to combat disinformation, preserve data integrity, and protect public

memory infrastructure online (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019).

5. Cultural and Civic Participation

Art, literature, theatre, and public

storytelling must be encouraged to democratize memory. Memory cannot be

preserved by archives alone; it must live through people—in festivals, murals,

oral traditions, and intergenerational rituals.

9.6

Global Comparisons and Strategic Lessons

Memory politics in Bangladesh is not

unique. The Turkish state’s repression of Kurdish history, Argentina’s Dirty